Proc Biol Sci. 2008 Jul 22;275(1643):1617-24.

Krushnamegh Kunte

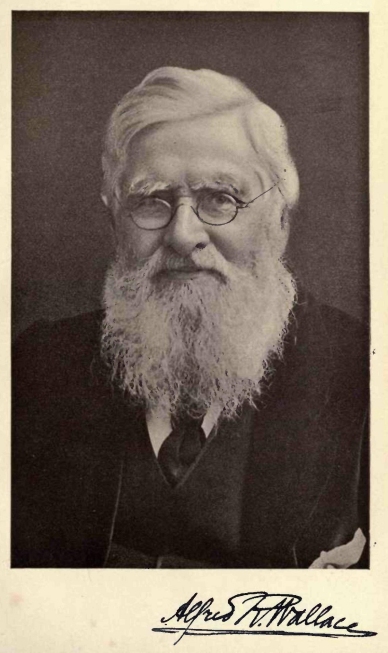

Section of Integrative Biology, University of Texas at Austin, 1 University Station C 0930, Austin, TX 78712-0253, USA Theoretical and empirical observations generally support Darwin's view that sexual dimorphism evolves due to sexual selection on, and deviation in, exaggerated male traits. Wallace presented a radical alternative, which is largely untested, that sexual dimorphism results from naturally selected deviation in protective female coloration. This leads to the prediction that deviation in female rather than male phenotype causes sexual dimorphism. Here I test Wallace's model of sexual dimorphism by tracing the evolutionary history of Batesian mimicry—an example of naturally selected protective coloration—on a molecular phylogeny of Papilio butterflies. I show that sexual dimorphism in Papilio is significantly correlated with both female-limited Batesian mimicry, where females are mimetic and males are non-mimetic, and with the deviation of female wing colour patterns from the ancestral patterns conserved in males. Thus, Wallace's model largely explains sexual dimorphism in Papilio. This finding, along with indirect support from recent studies on birds and lizards, suggests that Wallace's model may be more widely useful in explaining sexual dimorphism. These results also highlight the contribution of naturally selected female traits in driving phenotypic divergence between species, instead of merely facilitating the divergence in male sexual traits as described by Darwin's model.

Keywords

Batesian mimicry, polymorphism, female-limited mimicry, directional selection, stabilizing sexual selection, convergence